This is the online, accessible version of the exhibition Comics Beyond Sight, which was part of the 2024 Graphic Medicine Conference in Athlone, Ireland!

Installation views from the physical exhibition displayed at the Technological University of the Shannon in Athlone, Ireland, July 2024.

Comics Beyond Sight: Innovations in Accessible Comics for Blind & Low Vision Readers

Comics are increasingly called upon to convey public health information and are central in literacy development for young readers, yet for people who are blind or low vision, there are few means of accessing the comics form available today. This exhibition showcases the international efforts of innovators in this realm, assembled by the Accessible Comics Collective at San Francisco State University, with the expertise of blind access professionals guiding the field forward. Whether audio, tactile, or technologically mediated, these explorations in accessible comics raise bigger questions: What makes a comic a comic? How far from the original art form can a verbal translation stray while still honoring the artist’s work? The exhibition will provide opportunities to touch, listen, and explore, putting into practice the multimodal forms of access for which it advocates. By presenting a range of examples, from audio description to tactile comics, and from simpler layouts to highly complex artistic styles, we aim to demonstrate that all comics can be made accessible.

Website: https://spinweaveandcut.com/blind-accessible-comics/

Organizers Emily Beitiks and Nick Sousanis

ContentsPoster 1: Comics Beyond Sight: Innovations in Accessible Comics for Blind & Low Vision Readers

Poster 2: Blind Characters in Comics

Poster 3: Blind Creators Making Comics

Poster 4: Hearing Comics: Audio Description

Poster 5: Touching Comics: Tactile Graphics

Poster 6: Reinventing Comics: Haptics and New Technology

Poster 7: The ACC Design Competition

Poster 8: The ACC Design Competition

Poster 9: Now you try…

Poster 10: Call to Action & Bios

Physical Exhibition Descriptive Overview:

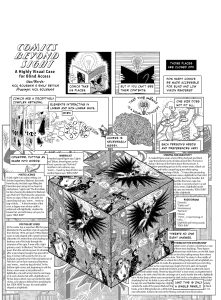

A series of ten posters, mounted on v-shaped walls, each a combination of curation text and comics-derived graphics, and adjacent tables provide additional hands-on items. Subtle design features on the posters nod to a comic book cover layout; one poster has a character corner box popular on Marvel and DC comics in the 70s and 80s, others feature the logo from the Accessible Comics Collective modeled after the DC Comics “Bullet” round logo, and another that plays off the “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” seal, which primarily appeared in comics in the second half of the 20th century. The color-scheme is minimal, primarily white backgrounds with pops of gray and a sky blue.

Click here for Accessible PDF of all the exhibition posters (This version has embedded description, but to best access the full description, see below, as character counts limited this version)

Poster 1: Comics Beyond Sight: Innovations in Accessible Comics for Blind & Low Vision Readers

Comics are a major form of popular culture and increasingly called upon as vehicles for conveying information from health to education, and central to literacy development for young readers. Yet for people who are blind or low vision, there are very few means of accessing the comics form available today. This exhibition showcases the international efforts of innovators in this realm, assembled by the Accessible Comics Collective at San Francisco State University, with the expertise of blind access professionals guiding the field forward. Whether audio, tactile, or technologically mediated, these explorations in accessible comics raise bigger questions: What makes a comic a comic? How far from the original art form can a verbal translation stray while still honoring the artist’s work? We invite you to explore, touch, listen and also question how you might participate in making more comics accessible in the future.

Reflections from the blind community: “When we’re talking about making comics accessible, we need to always remember, please, to center the person who this is made for. And that is blind people. Period.” — Podcast host, Access Advocate, and Voice Actor Thomas Reid

Images: A two-page black and white comic spread features a highly detailed artistic style. The title is “Comics Beyond Sight: A Highly Visual Case for Blind Access.” The drawings and text depict different ways of making comics accessible including audio description and tactile comics. To access an extensive description (audio and transcript) of this comic, visit: https://spinweaveandcut.com/mitcomic/

Caption: This physical comic created by Nick Sousanis and Emily Beitiks with accompanying audio track for MIT Technology Review, provides an overview of the approaches and challenges of translating such a highly visual medium into non-visual forms, and its accessible version sought to demonstrate how this could be possible, even with the complex artistic style featured here.

Text box: For the digital version of this exhibition, with visual descriptions for all images and accompanying audio: https://spinweaveandcut.com/accexhibition/

Poster 2: Blind Characters in Comics

Blind people have appeared inside comics for decades, blindness a problem to be cured with superpowers or a source of tragedy and melodrama. But comics today are evolving!

Corner Box description: All of the blind superheroes described below on the poster, with cutouts of their heads, closely laid out in a collage within a rectangle, referencing the common practice of putting the cast of characters in a “corner box” on comics in the 70s and 80s.

Daredevil (Marvel Comics): The most prominent of blind comics characters, Daredevil first appeared in Marvel Comics in 1964 and has been an ongoing character in his own comics, teamups, as well as film and TV. As a boy, Matt Murdock saves an old man from being hit by a truck but is consequently blinded by a radioactive substance that falls off that truck. The radioactivity not only robs him of his sight but enhances his other senses. As an adult, he becomes the superhero Daredevil.

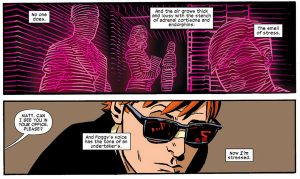

Description: A mosaic of Daredevil images. Daredevil is a man with light skin, sunglasses, and red hair. In his costume, he wears all red and has a cowl over his head with blacked out eyes and small devil horns. One image shows the way he experiences sight through his superpower senses, outlines of people in stripes of red.

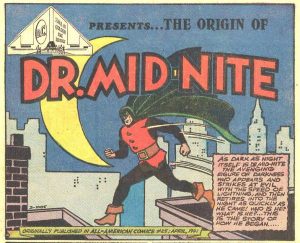

Dr. Mid-Nite (DC Comics): Often regarded as the first blind super character, Dr. Mid-Nite appeared in 1941 and starred in his own comics as well as the Justice Society of America. Blinded by a criminal’s grenade, Dr. Charles McNider discovered he could see in the dark. Arming himself with special goggles to see in daylight, smoke bombs, and a costume, he launched into a life of fighting crime.

Description: A vintage newspaper print comic shows a man with light skin and a green hood over his face pulled down past his eyes. Only his nose, mouth, and chin are visible. He has a yellow crescent moon on his forehead and is wearing rectangle goggles connected to the hood. He is on top of buildings jumping from roof to roof. A caption reads, “As dark as night itself, D. Mid-Nite the avenging figure of darkness who appears and strikes at evil with the speed of lightning and then retires into the night as quickly as he came! Who is he? What is he?…This is the story of how he began!” Originally published in All-American Comics #24; April 1941.

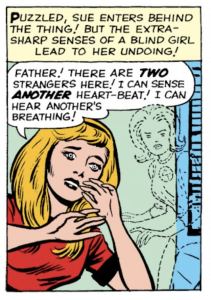

Alicia Masters (Marvel Comics): Alicia Masters has been a regular supporting character in the Fantastic Four comics since her first appearance in 1962, and is the longtime love interest of the rocky behemoth member of FF’s The Thing. Accidentally blinded at an early age by her supervillain father, but without superpowers, she becomes a sculptor, and her sense of touch and ability to feel a character’s interior self has been central to her appearances.

Description: A comic panel shows Alicia, a woman with light skin and blonde hair with bangs, and behind her, the outline of the invisible woman. Caption reads, “Puzzled, Sue enters behind the Thing! But the extra-sharp senses of a blind girl lead to her undoing!” Alicia says, “Father! There are two strangers here! I can sense another heart-beat! I can hear another’s breathing!”

Destiny (Marvel Comics): Destiny first appeared in 1980 and has been both an enemy and occasional ally to Marvel’s X-Men. Destiny’s powers of precognition emerged in adolescence and after writing down all the events set to happen in the near future for 13 months, she was left blind.

Description: A close shot of Destiny in the woods, with a shiny, gold full-face mask wearing an all-blue skin-tight superhero suit that reveals her full-busted figure.

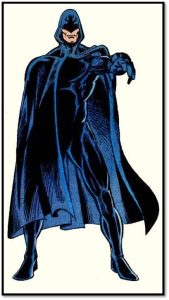

Shroud (Marvel Comics): Created in 1976, the Shroud dedicates his life to fighting crime after seeing his parents murdered by criminals. Upon finishing his training with a mysterious warrior cult, he is branded on the face with their mark, which removed his vision and replaced it with mystic extrasensory perception. He appears sporadically.

Description: Shroud wears a dark black and blue superhero suit and long cape with a fit physique. The only skin visible is his nose and mouth, and he has light skin. He stands in a powerful stance, one arm reaching out and pointing forward.

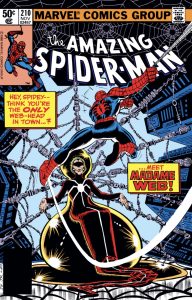

Madame-Web (Marvel Comics): Blind and paralyzed, the powerful telepath and clairvoyant Cassandra Webb has appeared periodically as a supporting character in Spider-man comics and other media since 1980.

Description: An old woman with light skin and greying hair pulled back. She has a red slight V-shaped band pulled across her eyes. Her lips are pulled down in a slight frown. On the cover of a comic, she sits surrounded by spiderwebs as Spider-Man is poised to confront her. Caption text reads, “Hey, Spidey – think you’re the ONLY web-head in town…? …Meet MADAME WEB!”

Blindfold (Marvel Comics): A member of the mutant superhero team the X-Men since first appearing in 2004, Blindfold is a mutant born with no eyes, who has powerful telepathic abilities.

Description: A young woman with light skin, long black hair, and a bandage wrapped across her eyes, smiles. Her belt holds the X-Men team logo.

Stick (Marvel Comics): Stick first appeared in Daredevil comics in 1981, a blind sensei who trains Daredevil and other related characters over the years.

Description: An old man with light skin wears a grey army-like suit and cap, with the cap coming down to cover his eyes. He has grey hair and stubble. A boy (young Matt Murdock – Daredevil) asks him, “Whaddaya got t’ say to that, old man? Huh?”

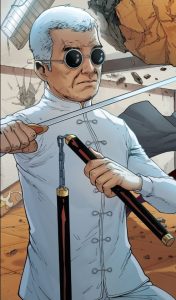

I-Ching (DC Comics): I-Ching first appeared in Wonder Woman in 1968, a blind martial artist who trained Wonder Woman when she lost her powers and has shown up on various occasions over the years to train other superheroes.

Description: An old man with light skin, short grey hair, and dark circle sunglasses stands holding nunchucks and a sword and wears a white jacket with a Chinese-style of cloth-button closures.

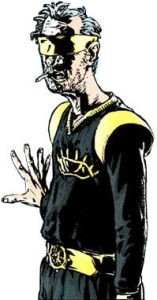

Blindshot (America’s Best Comics): Blindshot is a blind cab driver with “Zen senses” to take passengers “where they need to be.” He shows up in a few panels of the 1999 comic series Top Ten.

Description: An old man with light skin, a scraggly beard, short, balding grey hair, and a yellow blindfold across his eyes. He holds a cigarette in his mouth. While his outfit looks remotely superhero-esque, his whole demeanor is disheveled and withered.

Blindness Beyond Superhero Comics

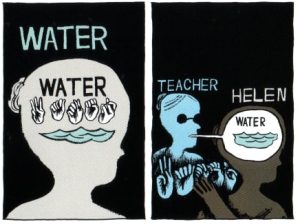

Hellen Keller (Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller by Joseph Lambert): This retelling of the early experiences of Annie Sullivan teaching Helen Keller sign language makes great use of the comics form to get at how this communication between them transpired.

Description: A silhouette drawing of the head of Helen Keller, as a little girl. Inside, the word “water” in both text and sign language, as well as a drawing of water.

Safia (My Aunt is a Monster by Remeina Yee): Young Safia had always wanted to go on adventures, but being blind, she didn’t think that would ever be possible. When she ends up living with her aunt (who happens to be a monster) – they go on a dangerous adventure together. Safia’s blindness is treated simply as part of her character and never the focus.

Description: Safia, a girl with brown skin and long hair with curls at the bottom. She wears a shirt and shorts and holds a white cane. She talks to her aunt, a blue creature with a goat-like head on a human body. She says, “Yes, Aunty. I promise. I’ll keep your secret,” and her aunt responds, “Thank you.”

Billie Scott (The Impending Blindness of Billie Scott by Zoe Thorogood): The story follows Billie Scott, a young artist who learns she is soon to lose her sight and sets out to find ten people to paint their portraits for an exhibition before she can no longer see.

Description: A young woman with light skin, freckles, short hair, and a frail build, drawn in greyscale. Three panels – the first, shows the word “GASP!” as an ominous darkness takes over the page. Second panel, Billie, now in front of the darkness, looking down at her hands says, “Oh-” and in the third panel, we see her view, obstructed by black spots as she looks down at her bandaged hand.

Reflections from the blind community: “Everyone was talking about this guy who could climb walls and I had no idea who [Spider-man] was. I asked my dad whether he could tell me about him, and he brought home a comic book and read it to me, and it’s just an amazing experience… I am over the moon, because I am understanding every single thing that’s happening… And, as I get older, my friends get more and more into comic books… and I can’t access them because there’s no way to scan them… no way to make the pictures tactile, and so I’m kind of stuck, I’m in limbo.” — Inventor & entrepreneur Matthew Shifrin

Poster 3: Blind Creators Making Comics

Representations of blindness are improving, and blind people are helping make change from on the inside. Blind people serve as script consultants to guide better representations in storylines and drawings of blindness, like how someone accurately navigates with a white cane. And there are blind comics creators now changing the conversation too, using the comics medium to best share their stories of navigating life in a vision-centric world.

M. Sabine Rear

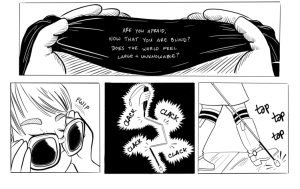

Bio: M. Sabine Rear describes herself as “a cartoonist and zine-maker, and the cute blind lady you gave your seat to on the bus.” Her work addresses disability, embodied politics, and public space, and seeks to trouble distinctions between “high” and “low” culture. This four page comic about blindness and ableist classroom practices was read at the 2017 Comics & Medicine conference.

Description: A short comic strip about students being blindfolded as an “empathy exercise” that causes more harm than good. Pictures of the helpless students pitying the poor blind people in contrast to a panel of Sabine confidently navigating with her white cane. To hear the full comic with the artist’s description, see the YouTube video here.

Link for more about Sabine’s work: http://www.michaelsabine.com/

Voices from the Blind Community: “Why do I bother making a visual medium, as someone with low vision? And why do I make it about myself? So I think those things are tied together for me. I will say that I don’t see myself reflected in a lot of visual media and particularly in comics …. I find it really empowering to bother to bring myself into that visual space and to engage with the aspects of visual media that I find interesting. …. We not only want to see ourselves in media…we don’t want to see ourselves misrepresented so we want to be talking about who’s in the room, making what choices about [how] the story gets told.”

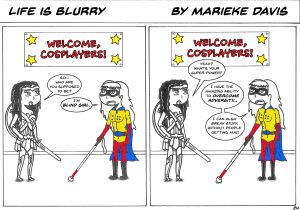

Life is Blurry by Marieke Davis

Bio: Marieke Davis is a legally blind, professional visual artist and author with right-side hemi-anopsia–missing right-side peripheral vision in both eyes, as a result of three brain surgeries to remove recurrent tumors since she was ten. While still an undergraduate, she began her graphic series, “Ember Black,” in print and audio formats, as well as a semi-autobiographical comic, “Life is Blurry,” an ironic view of the world from the perspective of a visually impaired visual artist, and won a VSA Emerging Young Artist Award from the Kennedy Center.

Description: Two people at a cosplay convention, a panel of “Life is Blurry.” One, dressed like Wonder Woman, asks who the other is supposed to be. She responds, “I’m Blind Girl,” a made-up superhero character wearing blue, red, and yellow, with the letters “BG” in braille on her shirt and holding a white cane. Wonder Woman asks, “Yeah? What’s your super-power?” and Blind Girl responds, “I have the amazing ability to overcome adversity…I can also break stuff, without people getting mad. Link: https://www.mariekedavis.com/

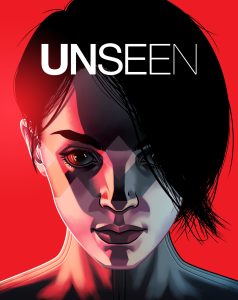

Unseen by Chad Allen

Bio: Unseen is a comics-inspired narrative created by Chad Allen and featuring the story of a blind assassin and heroine named Afsana. Written by a blind person, this comic has no visual form, made to be accessible and prioritize the blind listener’s experience, though sighted people are invited to check out Afsana’s journey too.

Description: A poster for UNSEEN. A somewhat realistic, geometric illustration of a woman with light skin and big eyes. She has short black hair in a pixie cut. She faces the viewer head-on intently. The illustration is on a solid, saturated red background. Link: https://www.unseencomic.com/

Voices from the Blind Community: “The comic medium offers some unique superpowers we should all get to experience!… Access to comics means access to education, to culture, to the intensity and power of sequential storytelling, and to a more creative, engaged and joyful way of spatial cognition and expression.” — Assistive Technology Coordinator, NY Public Library, Chancey Fleet

Poster 4: Hearing Comics: Audio Description

Audio adaptations offer the most developed and affordable form of access for comics to date. Some versions are more like radio dramas, which lean on sound and strong voice acting but drop the attention to the visuals. Others provide detailed or poetic language to translate comics visuals into words. While many comics start as written scripts, other comics are formed with words and pictures so closely intertwined that translating into language requires a lot of tough choices – an artistic process in and of itself!

Description: A pencil sketch at the poster’s top corner, shows a close-up of an ear with sound waves wafting in from different sides.

Fantastic Four #9

In this 2023 issue of The Fantastic Four, comics writer Ryan North and artist Ivan Fiorelli draw attention to comics’ inaccessible form and show the primary means of access for blind comics enthusiasts today: oral reading and improvised description from a loved one. As the script demonstrates, comics often begin with words and visual description even though it is not intended for blind access. View the full script here:

Ryan North’s script to Fantastic Four Issue 9, May 12th 2022

[North’s note to artist Ivan Fiorelli] We get to be a little more formalist in this one, since it’s Alicia’s turn to narrate! I did a bunch of research on how blind people read comics for this, because it felt wrong to have Alicia narrate a medium she can’t see without addressing that in some way. And it turned out super interesting, so now we get to have a big battle while also having a bit of fun with the nature of art and the medium we all love! Hope you like it. 🙂

Doom is still tangled up in Reed Richards, but now he’s hanging from a streetlight outside a police station, classic Spider-Man style. Reed has wrapped his body around the pole to be the net, holding him there. The other members of the FF are standing at the base of the telephone pole, shaking hands with the impressed police officers.

ALICIA NARRATION: Ben reads me my comics – he understands what I like to know about, and I can always ask him for more detail whenever I want.

DOOM: I HAVE DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY, YOU FOOLS!!!

REED: YOU CAN SCREAM ALL ABOUT IT ALL YOU WANT, DOOM…

REED: …ON YOUR POGO-PLANE FLIGHT BACK TO LATVERIA!

Back to reality, with our normal style. We see Ben and Alicia, at home (in NYC, before the farmhouse), reading a FANTASTIC FOUR comic with Doom and Reed comic on the cover. Ben and Alicia are on a couch – Ben’s sitting and reading, Alicia’s stretched out on her back beside him, using his leg as a pillow. The mood is pleasant, comfortable, relaxed. Alicia’s got her eyes closed, a slight smile on her face.

BEN: An’ Doom’s all tangled up in Reed an’ he’s yellin’ “I have diplomatic immunity, you fools!”

ALICIA: Heh.

ALICIA NARRATION: Or at least, he used to read me my comics.

To view the full script pdf, visit: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OfsWlA7kQ8UkkaXA6SlE9dcVyUV2Gs5V/view?usp=drive_link

Description:

Panel one: The Fantastic Four stand on the street after fighting Dr. Doom. Mr. Fantastic uses his stretch powers to wrap around Dr. Doom. Sue Storm says, “I’ve turned his retinas invisible, darling, so Doom can’t see us attack!” The Thing, Ben, says, “And I’ll clobber him if he even tries!” Human Torch says, “Not if I flame him first!” Over the panel there is a narration: “There’s this rinky-dink outfit in NYC that publishes coming inspired by the FF’s adventures. Those ones are my favorites.”

Panel two: Over this panel in what is now clearly a comic being read within the comic, the narrative caption reads: “Ben reads me my comics—he understands what I like to know about, and I can always ask him for more detail whenever I want.” Mr. Fantastic has Doom dangling by a lamppost next to a police station. Doom yells, “I have diplomatic immunity, you fools!!!” Mr Fantastic responds, “You can scream about it all you want, Doom.. on your pogo-plane flight back to Latveria!” The Thing, Sue, and Torch stand on the sidewalk below them talking to a cop.

Panel three: Caption: “Or at least, he used to read me my comics.” In a NYC loft, Alicia Masters and The Thing, Ben, are on a couch. Alicia leans against Ben while he holds a comic book in his lap. He says, “And Doom’s all tangled up in reed, and he’s yelling, ‘I have diplomatic immunity, you fools!” Alicia laughs.

Panel four: A close up of them. Ben says, “Those Marvel bozos always give Stretcho the best zingers, but really, it’s me with that pogo line.” Alicia says, “Uh-huh.” Caption says: These days, he’s not reading me anything.

Unflattening

Even the most visually complex work can tackle innovative forms of access, but it takes finesse, and there is no consensus inside of the blind community about the best way to put comics into words. What visuals can be rendered through words, and what can get lost in the translation? To engage the blind listener, how far from the original art form can description stray while still honoring the artist’s work?

To explore the possibilities, we created three different styles to describe the visually complex work of Nick Sousanis’ comic Unflattening – one developed by IDC Digital to offer a professional describer’s approach, another written by Sousanis with commentary that only the author could provide, and a third style, written by Emily Beitiks as narrative prose, breaking free from direct translation to provide the meaning of Sousanis’ work in an entertaining way.

Check out the table to see the three description approaches for Nick Sousanis’ Unflattening, and ask what opportunities and challenges each style provides. We shared all three descriptions with a blind expert panel for feedback – scan to access it! Link to descriptions with recorded audio: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/18mnx28eBm-eTJMoUjgeBLfDuv1TPRTiK

Link to panel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9y_bjUNs1Q

Description: A black and white comic page from Unflattening. We’ll provide you the description of this with a sample from each of the three different description styles. Version one: The professional audio description:

Describer Version 1:

The view displays the author’s eyes in two panels, facing directly toward us: first closed, then open.

Narrator: “In seeking new approaches for opening expansive spaces and awakening possibilities, let us look to our ways of seeing themselves, and how quite literally, the means to create perspective lies right between our eyes.”

Describer: One eye closes, then the other. A finger is held up in front of the text “which view is true?” As each eye is closed, the finger’s position shifts, so that it covers different parts of the text.

Narrator: “The distance separating our eyes means that there is a difference between the view each produces – thus there is no single, ‘correct’ view. This becomes evident by looking alternately through only one eye at a time…”

Continued as version 2: The creator’s version:

Immediately below these panels, on the left half of the page is a two-by-two grid, with the upper panels thin horizontal rectangles and the bottom panels squares with all sides the widths of the rectangles. Above the group of panels, the caption reads: “This becomes evident by looking alternately through only one eye at a time…” The top row rectangular panels depict the same set of eyes from the top of the page in each of these boxes. In the first one, the left eye is closed, and in the right one, the right eye is closed. In the square panels immediately below each set of eyes, there are two pictures of the same left hand with index finger pointing upward, only its location in the box has shifted to show the slightly different perspective from the vantage point of which eye you are using. There is text on a flat backdrop behind the index finger that reads, “Which view is true?”, though the view of the text is partially obscured by the raised finger.

Moving now to the right of this set of panels, there is a single horizontal panel sandwiched between two text boxes that shows this same scene yet again but from directly overhead – the person (on left side of the rectangular panel) holding their left hand up with index finger raised in front of the poster (on the right side of the panel) that reads, “Which view is true?” The caption directly above this horizontal panel reads: “And it is this displacement — parallax — which enables us to perceive depth.” And below the panel, another caption sums up the idea: “Our stereoscopic vision is the creation and integration of two views. Seeing, much like walking on two feet, is a constant negotiation between two distinct sources.”

Continued as version three: Narrative prose

To shift from the visual, the same experience can be approached through the aural, by putting on a song in stereo mode played with headphones. With just the left or right headphone in, the song is noticeably incomplete, yet when both play in tandem, the tracks unite so seamlessly that it is challenging to distinguish the separate perspectives presented the moment before. An additional example: by making a trip halfway around the sun, we essentially create two eyes a great distance apart. If we aim a telescope at far off stars, say in this case the constellation of Perseus (which appears as if all the stars comprising it are near each other in the flat sky) and then note the view of each star at six months apart against a far more distant cosmic backdrop that doesn’t change with the two views. The displacement of the observations from time one to time two allows us to calculate distances to these stars. Thereby unflattening the night sky to reveal the vast depths of space.

Additional description: On the exhibition table, there is a tactile page from Unflattening. A caption reads, “In this experiment, we created a pared down tactile diagram from Nick Sousanis’ Unflattening to accompany the descriptive audio track. It was not intended to get across the art on the page, but as a way to help blind readers stay oriented as they followed along with the audio description of this extremely complex and winding page layout. While the blind testers gained from the big shapes, the path, and the numbering on the captions, all detailed pieces were too small for a successful tactile experience.” The 8.5X11 swell paper with raised drawings shows a complex page, all captions and art details that are tiny have been stripped out to just show the shapes and flow of the comic page, like a twisting gameboard with each panel as a square for forward movement.

Voices from the Blind Community: “When it comes to audio description, what you add is just as important as what you leave out. You want description that is equal to people who can see the work as much as people who cannot. So to me, I think the best method is to describe the things that are moving the story forward.” — Comics Artist and Author Marieke Davis

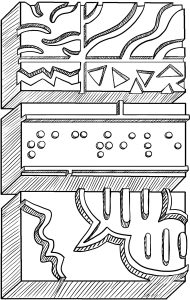

Poster 5: Touching Comics: Tactile Graphics

Tactile comics can convey the play and collisions between words and pictures across the page. But how many details can be felt before it all becomes too confusing? Touch these comics – what details make sense to you?

Description: A drawing at the top of the poster shows a comic panel grid, with each panel drawn to appear 3D with raised lines and featuring some snippets of braille.

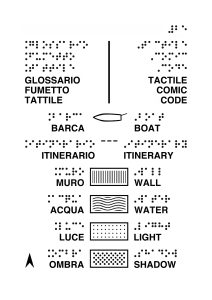

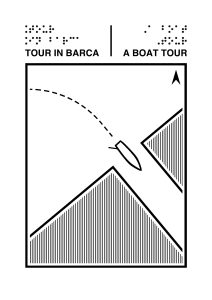

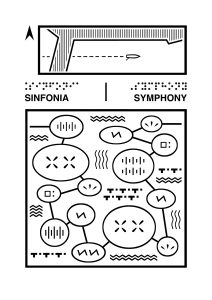

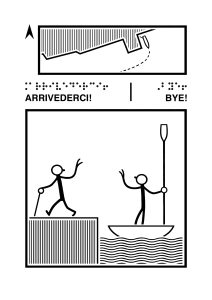

Max’s “A Boat Tour” (2017)

Max (a.k.a. Francesc Capdevila Gisbert) created this tactile comic, “A Boat Tour” to participate in Catalan’s contribution to the Venice Biennial. With braille and raised textures, he tells a simple story that introduces the reader to urban architecture and the sensory tourism of a Venetian boat ride, from the unexpected moments of silence on the water to the narrow squeeze between buildings. Check it out!

Description:

Page 1: Text provided in Italian, English and braille. Tactile comic code. With raised lines, a very simple outline of a boat, labeled “Boat.”. A dashed line, labeled “itinerary.” Thin vertical lines in a box, labeled, “Wall.” Wavy lines, “Water.” Sparse, evenly dispersed dots as “light.” And finally, “Shadow” as denser, bigger, and less even dots.

Page 2: Text title reads, “A boat tour.” A boat on the water, dotted lines showing the path it’s come from as it navigates into a canal between two walls.

Page 3: Title reads, “Symphony.” The boat continues on a large structure on one side and open water on the other, with varying tactile patterns to show different ambient city sounds, such as “solace,” “bells,” and “voices,” the symphony of sounds in tactile form is plentiful.

Page 4: The boat is leaving the dock. Two stick figures wave to wave to each other, one person with a cane on land and the other on a boat holding an oar. Text reads, “Bye!”

Ilan Manouach, Shapereader

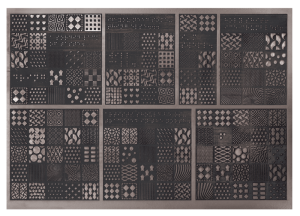

Conceptual comic artist Ilan Manouach created Shapereader, which offers an entire vocabulary of different abstract geometric shapes on laminated metal plates. Some shapes refer to characters, others to actions, and some are narrative props. Exploring Shapereader means that the reader gets acquainted with this whole set of symbols first, and then reads them as a story. The experience puts both the sighted and blind reader on equal footing, as they both are encountering this alien yet familiar code for the first time.

Description: A tactile board of different patterned raised shapes on metallic plating in a grid formation, like a tactile quilt pattern in dark black and grays.

Michael Sutjiadi, “The Adventure of Jarrett and Friends.”

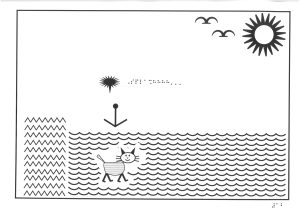

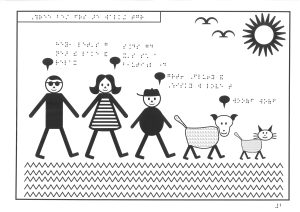

Michael Sutjiadi created “The Adventure of Jarrett and Friends” as his Masters project to train young deaf-blind readers on how to navigate comics. It begins with tactile and braille instructions to orient the reader to the comics form, then lays out a story. To make the tactile graphics usable required each comics panel to take up a whole page.

Description:

Page 1: A raised line drawing of a cat hovering above water, with an arrow pointing down. Text in braille says, “Splash!”

Page 2. Simple drawings of stick figures walking under the sun. A man with glasses says, ““Hey, let’s go near the lake and relax,” a woman wearing a dress replies, “Sounds good, it’s such a beautiful day.” A young kid wearing a baseball hat, adds, “Great! Fluffy and Whisky will love that.” Fluffy, the dog, says, “Woof! Woof!” and the cat is silent.

Reflections from the Blind Community: “While I would like to dislodge the notion that blind people rely exclusively on touch perception to know the world, I admit that whenever I have the opportunity to get my hands on art, I leap at the chance.” — Georgina Kleege, author of More than Meets the Eye: What Blindness Brings to Art, pg. 60

Poster 6: Reinventing Comics: Haptics and New Technology

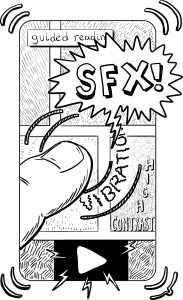

As comics and multimedia creators think about accessibility for blind consumers, a range of modalities might be considered when rendering comics for nonvisual consumption. With new and emerging technological advancements, one potential gain is to give the blind user more navigation control over how they explore a comic.

Description: At the top of the poster, an illustration of a finger touching a comics panel on a phone screen, which causes ripples that indicate and say “vibration” and a sound bubble emanates from it saying, “SFX!”

Project Daredevil: “Project Daredevil,” a project by Matthew Shiffrin, Tina Quach, and Dan Levine with MIT immersive virtual reality, proposed the creation of a helmet to make a wearer feel like the superhero while listening to a 3D sound audio comic.

Description: An adapted motorcycle helmet with colorful electrical wires coming out of it sits on a workbench.

Sketchnote on Emerging Technologies: This sketchnote was developed live by Sam Hester during a panel on making comics accessible through emerging technologies by the Accessible Comics Collective on August 12, 2021. (See Hester’s comics and graphic recording here: https://www.the23rdstory.com)

Description: A drawing and explanation of haptics, tactiles, and sonification. Smiley faces on the page post questions, “What does accessibility mean in context of comics?” another adds, “Allowing the reader to answer and ask questions about the text,” and a third adds, “Not just the what, but the why and how.” Large headings draw attention to text that reads, “The Absence of Barriers” with a connected path that reads “A shared social experience.” Infographic style boxes provide definitions:

Haptics = Feedback that you can touch or feel, not just through the fingertips.

Tactiles = Using our fingers to feel a surface.

Sonification: The art and science of representing data using sound.

Monarch: New innovations like HumanWare’s The Monarch, a tactile braille device, might allow tactile comics to grow. Roughly the size of a small laptop with a 10-line by 32-cell refreshable braille display, pins raise to create the tactile representations, and then with the click of the button, they transform into the next tactile picture.

Description: An overhead photograph of a Monarch machine on a wood table. A child’s hands are exploring it, a raised image of a truck.

Vizling: Darren DeFrain and Aaron Rodriguez’s Vizling app makes comics accessible through an interface that mixes haptics with voiced description, allowing users to explore and navigate the comic page by touch. They were one of the prizewinners of the ACC Design Competition, which brought the app creators together with low vision comics creator Marieke Davis and blind experts who have helped guide Vizling’s development. Learn more and test it out!

Description: A drawing of a finger swiping across a very basic comic page with two stick figures in dialogue from panel to panel. A “zzt” sound bubble is next to their finger. Link: https://vizling.org/

Vizling testimonial: “I felt like I was reading a comic again! When I was a kid in Brazil there was a comic called Mauricio Da Souza that I loved and I felt that experience again. I felt like I was immersed in the story.” — Co-owner of Adaptive Technology Services Silvana Rainey

Poster 7: The ACC Design Competition

The Accessible Comics Collective (ACC) brings together comic makers, access professionals, and blind comics fans for dialogue and generative collaboration to fuel the development of this nascent field. Since 2021, we have hosted four convenings, reaching hundreds of participants across the globe eager to see this field blossom. Each event has prioritized centering the expertise of blind people in our programming.

The ACC launched a competition in the summer of 2022 to motivate new innovations in access, inviting proposals from teams (each had at least one blind member) to either adapt a traditional comic into an accessible version or produce a new comic “born accessible.” Then, they received feedback during a public panel from blind experts to support their designs.

Seeing Inbetween by Illi Anna Heger and Rae Lanzerotti

Eavesdrop on two nonbinary queer people chatting about spaces in between and navigating accessibility. This queer comic conversation, a collaboration between Rae Lanzerotti and Illi Anna Heger, is about seeing and being seen in between abilities, genders, and spaces. This comic is accessible in different ways: play audio or read text transcripts, and view visual images or get descriptions. Choose the complete audio version, the full text version, or click through the multimodal elements of audio, text, visuals, and embedded alt text.

Link for the full comic with audio and alt text: https://www.annaheger.de/inbetween/

Description:

Image Description 1: The title at the top of the comic panel reads: Seeing Inbetween. Two people are hovering over the arc of the blue earth, with Europe and the USA in focus. Their names and cities are written next to them. The comic has black line artline-art with pink, yellow, and blue coloring and gray tones. On the left, Rae Lanzerotti, from San Francisco, wears an eyepatch, pink headphones, a white shirt, yellow pants and blue shoes. On the right, Illi A. Heger, from Munich, wears glasses, blue headphones, a yellow shirt, white skirt and pink boots and looks over at Rae.

Image 2 Description: Rae and Illi sit cross-legged above the earth, gesturing broadly as they speak. The darkening sky behind them fills with overlapping words. As the words fade into the background, they read: long-distance, she, refueled, up, hourglass, and other fragments. In between Illi and Rae, their conversation forms a swirling circle of blue, yellow and pink lines.

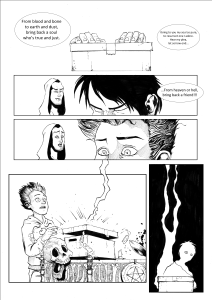

Punk’s Undead by Casey James O’Ceallaigh and Brian Rutherford

Casey James O’Ceallaigh and Brian Rutherford collaborated to develop high-quality audio description to accompany Casey’s comic, Punk’s Undead.

Description: A sample of panels from Punk Undead, which has a dark, almost gothic style in detailed black and white line drawings. The team developed high quality description for this, and we encourage you to check out here, link for audio: https://youtu.be/Ebur7KmBqWs?si=kh8U93-Di4sP5r2hdddsss

Reflections from the Blind Community: “There is a lot of room to grow… the only way for us to find out [how] is to keep making descriptions and keep getting feedback from community as much as possible.” — Digital Accessibility Coordinator Walei Sabry

Curation text: After starting this project, Brian Rutherford unfortunately passed away in February of 2024. On display on the exhibition table is Casey’s eulogy to Brian, which we offer below as it speaks to the unexpected joys that come from thinking about access as a creative process:

Brian Rutherford

January 07, 1972 – February 01, 2024

My name is Dr. Casey O’Ceallaigh, and I was one of the recipients of the Accessible Comics Award in 2022. Recipients were encouraged to work with community members who were blind or had low vision, and the grant’s organizers could assist matching recipients with community members. By chance, I was matched up with Brian, who unfortunately passed this past February.

Brian was such a personable man, dedicated advocate, and lover of musical theater that I could not help but want to take up my day learning from the depth of wisdom that Brian had. The first time I spoke over the phone with Brian–and every other time we spoke thereafter, the call lasted for nearly two hours. Sometimes, we would intend to talk about the accessible comics project and would end up talking at length about different productions of our favorite shows.

Within a few months of working with Brian, I decided to fly out to visit him for a weekend so he could show me all of the theaters and museums he helped review for accessibility. Brian was a beloved member of so many communities where he lived. That is when I truly learned about Brian’s wicked sense of humor and his ability to find a way to laugh through everything.

The first day I met him, we went to see a visual description showing of Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 and on the way back home, the route he knew how to take back was shut down. Both of our phones couldn’t connect to any service, and he managed to keep us both laughing as I said the names of backroad streets on the outskirts of Pittsburgh until he recognized a crossroads that could get us back.

That weekend, I also got a glimpse into how much society devalues accessibility, and how needlessly inaccessible our world is. Transport services are underpaid and understaffed, leading to most of Brian’s scheduled transportation being late, sometimes by up to thirty minutes. They’re overworked, so they misread instructions clearly stating which exit of a large building Brian would wait at, leaving Brian waiting for over an hour after his scheduled pickup time because the driver is searching for him at all the other entrances. Obstruction on sidewalks forced Brian to walk in streets full of potholes. He had to wait several days for his cable to be fixed because the customer service representatives had no way to explain how to reset it himself that didn’t require vision, so he had to wait for a sighted person to make the phone call instead. In three days, I witnessed so many unnecessary obstacles Brian had to face in part due to apathy, accident, negligence, or unthoughtfulness.

Despite this, Brian never failed to educate, advocate, and motivate. The resolve he showed was only matched by the wisdom that came from bearing the weight that comes from such resolve. And yet, he always found a way to get someone to smile. In Brian’s memory, I ask of you to love harder and to strive stronger to broaden your perspective to try and understand as much of the diversity of the human experience as possible. That way, we can more readily reshape our world to have as little barriers as possible for everyone regardless of ability. That is the world Brian fought so hard for, but never got to experience. However, Brian found a way to be happy through anything, and I know it would have brought him such joy to know his memory inspired that world to be made at all.

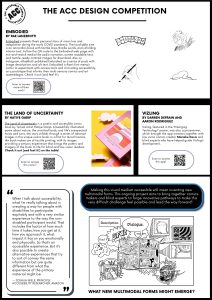

Poster 8: The ACC Design Competition

Embodied by Rae Lanzerotti: Embodied presents Rae’s personal story of vision loss and adaptation during the early COVID pandemic. The touchable zine is an accordion book with tactile lines, Braille words, and unfolding interior text. Follow the QR code to the Embodied web page with mix-and-match media like audio narration, screen readable text, and tactile-ready contrast images for download. Also on Instagram, @hatiotti published Embodied as a series of posts with image descriptions and alt text. Embodied is Rae’s first memoir comic to experiment with access tools and innovating accessibility, as a prototype that informs their multi-sensory comics and art assemblages. Check it out (and feel it!).

Link: https://www.rlanzerotti.com/stories/embodied

Description: Black and white raised drawings with a simple line-art style. In one, a hand crumples up paper. In another the hand holds a pen and draws a little. In the third image, the artist’s body is on their knees in a yoga pose, leaning forward with their head on the ground. For the artist’s complete descriptions, visit the link.

The Land of Uncertainty by Hatiye Garip:

The Land of Uncertainty is a poetic and accessible comic book by Turkish artist Hatiye Garip. A beautifully illustrated poem about nature, the unvisited lands, and life’s unexpected twists and turns, the story unfolds through a series of abstract images in this unique comic book. In a first for Good Comics, the book makes use of tactile printing, with its images providing a sensory experience that brings the poetry and imagery of the book to life for blind and low-vision readers. Check it out (and feel it!) on the table!

Link to comic: https://goodcomics.co.uk/shop/pre-order-the-land-of-uncertainty-by-hatiye-garip-audio-and-digital-bundle/

Description: Copies of “The Land of Uncertainty” sit on a yellow table with paper clouds. The cover is pink, yellow, and red with various abstract shapes, showing a raised texture to the cover.

Written & Drawn by Hatiye Garip

Text-only, descriptive version written by Tuba Kaya, co-written by Hatiye Garip. Edited by Lisa Madl and Paddy Johnston

Book text narrated by Áine Kelly-Costello

Descriptions narrated by Paddy Johnston

Field recordings captured by Hatiye Garip

Audio version, including ambient music, produced by Paddy Johnston

Vizling by Darren Degrain and Aaron Rodriguez:

Vizling, featured in the “Emerging Technology” poster, was also a prizewinner, which brought the app creators together with low vision comics creator Marieke Davis and blind experts who have helped guide Vizling’s development. Link: https://vizling.org/

Additional Curation Text: Making this visual medium accessible will mean inventing new multimodal forms. This ongoing project aims to bring together comics makers and blind experts to forge innovative pathways to make this very difficult challenge feel possible and lead the way forward!

What new multimodal forms might emerge?

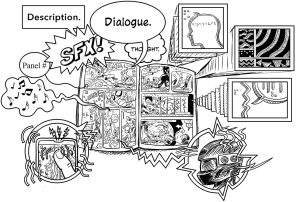

Description: A black and white drawing by Nick Sousanis of a comic book with various comics accessibility modalities pouring off its pages. Out of the comic book come speech bubbles with dialogue, sound effect bubbles, music notes, braille in a person’s head, tactile ridges, a haptic and responsive phone app, and an adapted helmet with sound.

Reflections from the Blind Community: “When I talk about accessibility, what I’m really talking about is creating a way for people with disabilities to participate equitably and with a very similar experience to the way the non-disabled participant would. That includes the factor of how much time it takes, how you get at it, how you approach it, what impact it has on you emotionally and physically. So that’s an accessible experience. But it’s also possible to create alternative experiences that try to sort of convey the same information but are quite different from what the experience of the primary material might be.” — Joshua Miele, Principle Accessibility Researcher, Amazon

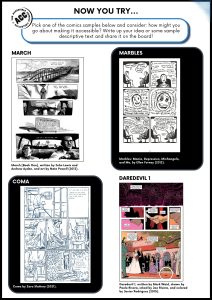

Poster 9: Now you try…

Pick one of the comics samples below and consider: how might you go about making it accessible? Write up your idea or some sample descriptive text and share it on the board!

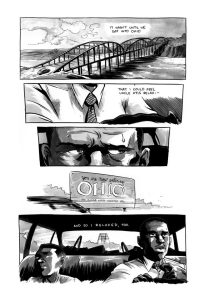

March [Book One], written by John Lewis and Andrew Ayden, and art by Nate Powell (2013).

Description: A black and white comic page arranged in a series of horizontal panels, five in all down the page. A car approaches a bridge over a body of water. In the car, an older Black man sits in the driver’s seat. He wears a white button up shirt and patterned tie. Sweat drops down his forehead. The first three panels go from page-width, to narrower, to narrower on the man’s eyes and forehead. This fourth panel has no border: The car passes a sign reading, “You are now entering Ohio.” Final panel, page width again: In the passenger seat, a young Black boy looks out the window. Internal thoughts read, “It wasn’t until we got into Ohio that I could feel Uncle Otis relax—and so I relaxed, too.”

Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michangelo, and Me, by Ellen Forney (2012).

Description: A black and white comic arranged as a two panel wide by three tall grid, all of equal square or near square dimensions. A woman with short hair, author Ellen Forney, sits in therapy. In multiple panels, words swarm around her head, a dizzying blend of words and swirls. A drawing of her face becomes less coherent and more sketch-like and also manic before going back to normal. As this manic-episode developes, the panel borders themselves disappear and the stream of words becomes the border before returning to lined off panels at the end again.

Therapist: How’s work?

Ellen: Great! I guess. I’m so busy! I made a list of everything—here—my weekly comic, catalog drawings for Toys in Babeland, illustrations for the Gay Men’s Health Guide, a thing for Ben is Dead—that’s a zine—buy a wig to wear to a big COCA art opening, promote my book, frame some posters for a show.

Therapist: That’s a lot.

Ellen: That’s normal for me, thought, all these different kinds of projects… and the sexy stuff is kind of my niche, all that sex-positive and queer stuff, which has tio to with me, too, being really out, kind of a bisexual role model, because there’s anti-bi attitudes even in the queer community… we need liberal identity politics… and anyone who can be out should be out, people are social animals, and I want to help people believe in themselves…

Therapist: Sounds like you’re very busy. Are you getting your work done?

Ellen: Well, yeah, I guess. But are you asking about my income? Most Of my work is more like creatively fulfilling. Something always works out. I feel like the universe will provide. Money is an abstraction.

Therapist: Well, remember an abstraction won’t pay for your groceries though.

Ellen: Meh.

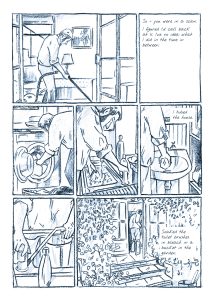

Coma by Zara Slattery (2021).

Description: A blue and white comic, sketchily drawn in a neatly arranged grid of seven panels. A man does chores in his house: vacuuming, laundry, dishes. Internal thoughts read, “So, you were in a scan. I figured I’d call back at 11. I’ve no idea what I did in the time between. … I tidied the house. … Soaked the toilet brushes in bleach in a bucket in the garden.”

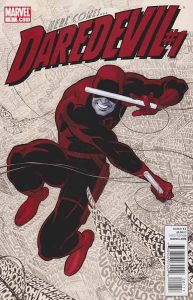

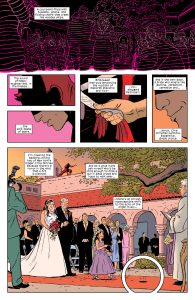

Daredevil 1, written by Mark Waid, drawn by Paolo Rivera, inked by Joe Rivera, and colored by Javier Rodriguez (2015).

Description: A Daredevil comic. At a wedding, Daredevil scans the crowd seated for the wedding, the opening panel is borderless and shows the way he experiences vision through his radar supersense, outlines and crosscuts of people without details. Caption reads, “The courtyard filled with tuxedos, gowns, and folding chairs that creek like wooden ships.” The next two panels show Daredevil’s head looking down on the crowd but a panel gap breaks up the picture and obscures where his eyes would be, captions in each read, “The sound of happy laughter and, in the breeze…” “the salt-taste of tears.” The next panel is a close shot of his ungloved hand grasping the paper wedding invitation, caption reads, “Embossed linen-pulp announcing the nuptials of Deborah Giacomo and Vict… no…Vincent Petrocelli.” Next panel, a close shot of Daredevil’s masked face, the caption blocking his covered eyes and a thin smile showing, caption reads, “And in the very back, a bride who smells like jasmine, cardamom, carnation and …lemon. Clive Christian perfume. Expensive. Great Choice.” Now, a half-page spread shows the full scene, the bride walks down the aisle linked with her father’s arm, guests joyously take her in, and on the church rooftop above is Daredevil crouching in his red bodysuit, surveying the scene. Captions read, “I’m crashing the wedding uniting two of New York’s bigger crime families because there’s a rumor in the wind that a hit is planned. dAnd as I once more ask myself who’d be idiot enough to draw a gun in this crowd and hope to walk away…there’s an almost imperceptible shift to the echo of the organ music…” There’s a small circular panel inset in the bottom of this larger panel, drawing the reader’s focus to an ominous black spot appearing on the red path that the wedding party is walking towards.

Poster 10: Call to Action & Bios

Thank you for learning with us about accessible comics and the unfolding possibilities! The Accessible Comics Collective needs your help to make this practice the norm, not the exception it is today.

Three guiding values lead the way forward:

-

There’s no “one size fits all approach” to this work, as there is much diversity in what blind readers want when accessing a comic. We need to bring the same artful creativity that we bring to comics to comics access.

-

Good access will engage blind listeners while still honoring the comics form. It’s an act of translation.

-

The expertise and feedback of the blind community must be central in leading the way forward.

Learn more and get involved with the Accessible Comics Collective: https://spinweaveandcut.com/blind-accessible-comics/

Contact:

- Nick Sousanis (sousanis@sfsu.edu)

- Emily Beitiks (beitiks@sfsu.edu)

Reflections from the Blind Community: “[Blind people] know that we can create demand and normalize access to comics because our community has done that same thing for text on the web, for the mobile web, for museums, and for so many other things. We know what we need [in order] to shape a more accessible future for comics: We need an informed conviction that the media matters—we can talk about that with stakeholders. We need a working knowledge of how meaningful, satisfying scalable access can happen—and what access techniques are suitable for different types of comics and situations. And more than anything, we need each other to stay in touch and also to amplify what we discovered today so much that every blind adult and child, every educator, every parent, every ally, every publisher knows that comics are for everyone and knows exactly what is possible.” — Assistive Technology Coordinator, NY Public Library, Chancey Fleet

Text: This sketchnote was developed live by Sam Hester during the closing keynote at a symposium by the Accessible Comics Collective on August 12, 2021.

Description: This is a drawing made of words and a few pictures. It’s drawn with black markers on white paper and there are some light blue and yellow highlight colors. In the top left corner there is a drawing of Chancey Fleet’s face next to a sign that asks her question: “How is this work necessary and valuable enough to compel our resources?” The page features some word bubbles that offer her reflections on that question, along with another question that she says members of this community should be prepared to answer: “Why do blind people need comics?” The word bubbles are surrounded by a few lines, colours, shapes and simple pictures of people that (I hope up) give some visual relief to an image that is mostly made of words. At the bottom of the page are some of Chancey Fleet’s closing messages, including: “Spread the word!” And “We need each other!”

About the Curators

In an effort to explore possibilities for access in comics, Nick Sousanis and Emily Beitiks, along with our colleague Yue-Ting Siu, came together in an interdisciplinary collaboration at San Francisco State University. After discovering how complex this work is, we started regularly collaborating to host public events to dive into the possibilities, and called this network of comic makers, access professionals, and blind comic enthusiasts, the Accessible Comics Collective.

Emily Beitiks is a leader in promoting creative forms of access in her role as the Interim Director of the Longmore Institute on Disability at San Francisco State University, learn more at LongmoreInstitute.sfsu.edu. Nick Sousanis is the author of Unflattening and runs the comics studies program at San Francisco State University. You can learn more about his work on his website, SpinWeaveAndCut.com.

Graphics: Layout by Shaina Ghuraya, spot illustrations by Nick Sousanis.

Image Descriptions written by Nathan Burns, Emily Beitiks, and Nick Sousanis.

This work has been possible thanks to the support of an incredible network of colleagues who have participated in our Accessible Comics Collective work: Jose Alaniz, Jane Burns, Nathan Burns, Chad Allen, Rick Boggs, Canan Çam Yücel, Áine Kelly-Costello, Ann Cunningham, Marieke Davis, Darren DeFrain, Chancey Fleet, Daniel Fontaine, Gina Gagliano, Hatiye Garip, Shaina Ghuraya, Max (a.k.a. Francesc Capdevila Gisbert), Rozi Hathaway, Illi Anna Heger, Sam Hester, Paddy Johnston, Esra Kaya, Georgina Kleege, Rae Lanzerotti, Anil Lewis, Lisa Madl, Ilan Manouach, Nefertiti Matos, Scott McCloud, Sky McLeod, Joshua Miele, Ryan North, Casey James O’Ceallaigh, Sile O’Mondrain, Charity Pitcher-Cooper, Silvana Rainey, Thomas Reid, Aaron Rodriguez, Brian Rutherford, M Sabine Rear, Walei Sabry, Matthew Shifrin, Joe Strechay, Ed Summers, Michael Sutjiadi, Frank Welte, Samuel C. Williams, and Stanley Yarnell.

Particular thanks to our former co-collaborator Yue-Ting Siu!

Thanks as well to organizational support from:

-

IDC Digital and in particular Eric Wickstorm, Liz Guzman, and Dakota Green

-

The College of Liberal and Creative Arts at San Francisco State University

-

MIT Technology Review and in particular Mat Honan and Allison Arieff

-

All the organizers of the 2024 Graphic Medicine Conference!

See all of our past events and resources on accessible comics here https://spinweaveandcut.com/blind-accessible-comics/!